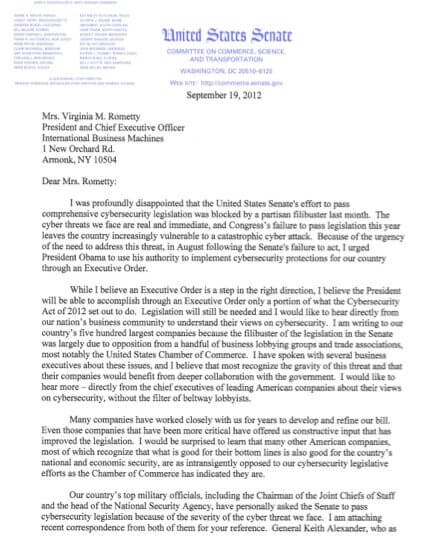

Having failed to muster the necessary support to pass his cybersecurity bill in this election year, and on the heels of a leaked draft of an Executive Order on the subject, Senator Rockefeller has taken another approach to try to get big business behind his efforts. As  mentioned here last week, in a letter to the CEO of IBM, Virginia Rometty, Senator Rockefeller stated that he was “writing to our country’s five hundred largest companies because the filibuster of the legislation in the Senate was largely due to opposition from a handful of business lobbying groups and trade associations, most notably the United States Chamber of Commerce.” Senator Rockefeller stated that he wants to hear directly from the Fortune 500 companies, “without the filter of beltway lobbyists.”

mentioned here last week, in a letter to the CEO of IBM, Virginia Rometty, Senator Rockefeller stated that he was “writing to our country’s five hundred largest companies because the filibuster of the legislation in the Senate was largely due to opposition from a handful of business lobbying groups and trade associations, most notably the United States Chamber of Commerce.” Senator Rockefeller stated that he wants to hear directly from the Fortune 500 companies, “without the filter of beltway lobbyists.”

After detailing in his letter the need for a comprehensive approach to shoring up the nation’s cyber-security – a need that, frankly no one disputes (rather there are certainly competing views on how best to do so, see here and here for a couple of our previous posts), the Senator set forth eight questions to which he wants businesses to answer by October 19, 2012.

On a general level, the Senator’s approach here seems more like a stick-up than a sincere attempt to understand the opposing views. If it were the latter, he could have obtained the information he seeks in a much less combative/public way. Nevertheless, we have given considerable thought to these issues and are happy to share that knowledge.

Below are the questions the Senator posed, along with some of our thoughts on each.

1. Has your company adopted a set of best practices to address its own cybersecurity needs?

We certainly hope and expect that most, if not all, of the companies on the Senator’s list have, at some level, considered their cybersecurity needs, vulnerabilities and potential solutions. Because the threats and needs differ across different industries, however, we have seen significant variability in both the form and the substance of the practices put in place by different companies. Similarly, the notion of “best practices” can be misleading since there is no one-size-fits-all solution, which is one of the main objections to Senator Rockefeller’s proposed legislation.

2. If so, how were these cybersecurity practices developed?

Asking a company to share how their cybersecurity practices were developed could be problematic. This was similar to what Adam Putnam asked companies to do in 2003 in a draft bill that he circulated. It was met with significant resistance due to the sensitive nature of this kind of information. Any discussion on these matters should focus generally on the standards and methodologies used, not on the detailed practices themselves.

3. Were they developed by the company solely, or were they developed outside the company? If developed outside the company, please list the institution, association, or entity that developed them.

Again, providing such information could present risks, both from a security and contractual perspective. Specifying the standards and methodologies, however, would seem to be fine.

4. When were these cybersecurity practices developed? How frequently have they been updated? Does your company’s board of directors or audit committee keep abreast of developments regarding the development and implementation of these practices?

In a perfect world, all companies would be proactively addressing their cybersecurity practices with unlimited budgets and, therefore, will be confronting these issues before any type of incident. But the world is not perfect, and it is not uncommon that such efforts are forced on a company due to a breach or perceived incident or the very public troubles of others similarly situated. This is the most frequent occasion for the board or audit committee to get involved.

Whether a company is starting from scratch or is performing a periodic review, getting an experienced third-party, who encounters these issues daily and has seen what works and the possible pitfalls associated with what doesn’t, to guide your internal team’s efforts is advisable. Further, regular updates are important since the security environment (both internally and externally) changes frequently.

5. Has the federal government played any role, whether advisory or otherwise, in the development of these cybersecurity practices?

The federal government can often be found to be playing a role in the cybersecurity practices of a company. Sometimes such involvement is direct (e.g., when the entity plays a role in the Defense Industrial Base (DIB) or when it is involved with critical infrastructure). In other cases, the government may have an indirect role in the cybersecurity posture of a company. For example, NIST has produced an excellent set of Special Publications known as the 800 series (see http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/PubsSPs.html). These can provide an excellent starting point for companies looking to develop or implement various cybersecurity capabilities. But for many companies, the response to this question will be a simple “no.”

6. What are your concerns, if any, with a voluntary program that enables the federal government and the private sector to develop, in coordination, best cybersecurity practices for companies to adopt as they so choose, as outlined in the Cybersecurity Act of 2012?

Depending on one’s function, role, or philosophical position, there could be a variety of concerns. First, a voluntary program may result in many competitors not participating, which would simply increase costs for the company voluntarily complying while the other company would not be spending equivalent amounts. Second, a voluntary program that puts in place a set of practices as a ‘floor’ runs the risk of becoming the ceiling that no one ever goes beyond. Finally, if a static set of practices that gets put in place and does not evolve with changing threats, it becomes useless very quickly.

We believe that the concept of the federal government and the private sector voluntarily sharing information with each other so that both can develop best practices that work for their own situations is a laudable goal and would assist both sides of the equation in combating cyber threats. However, whether the Cybersecurity Act of 2012 is the right approach is debatable. Some argue that the Act would inappropriately regulate a range of U.S. infrastructure cyber networks, without sufficient privacy safeguards for the data contained therein, and at the expense of innovative approaches to addressing constantly changing cyber threats. What may be the appropriate best practices for IBM, for example, may not fit the business model and risks faced by a different type of business, such as Allstate, which may be completely different than what is appropriate for Philip Morris, which may be different. Best practices are very situation specific.

7. What are your concerns, if any, with the federal government conducting risk assessments, in coordination with the private sector, to best understand where our nation’s cyber vulnerabilities are, as outlined in the Cybersecurity Act of 2012?

We question whether, however well meaning, any government risk assessment framework can remain nimble enough to keep up with the ever-changing methods used by scofflaws or the ever-changing marketplace of business models that constantly create new vulnerabilities. Because of this, we are concerned that companies might be lulled into a false sense of security that they are meeting the government’s requirements, and thus no more need be done. On the flip side, those who do go beyond what a government risk assessment might show could be open to second-guessing if their practices are different from those adopted by the government.

8. What are your concerns, if any, with the federal government determining, in coordination with the private sector, the country’s most critical cyber infrastructure, as outlined in the Cybersecurity Act of 2012?

Most frequently, our clients and contacts express concern over certainty. Without clearly drafted language about what constitutes critical cyber infrastructure, many companies might not know until too late that they are subject to or should be deploying any of the mechanisms described above. Again, one size doesn’t fit all. Just because an entity has been declared a part of the critical infrastructure doesn’t mean it will need to deploy the same security as the next entity to be declared part of the critical infrastructure.

Ultimately, we have particular views on how companies should best protect themselves and would be happy to assist your company in either responding to the Senator’s inquiry (if you received the letter) or thinking through your security and liability concerns (whether or not you received the letter).